Although it’s been a decade since the historic flyby of the New Horizons probe, analysis of the data it gathered continues to yield revolutionary discoveries. The latest research suggests that Pluto, once home to a subsurface ocean of liquid water, is slowly freezing from the inside. The evidence for this process doesn’t come from direct temperature measurements, but is instead written into the icy crust of the dwarf planet. For a detailed look at these findings and what they reveal about Pluto’s interior, see our article on The Heart of Pluto is Cooling: Evidence of a Freezing Ocean Written on Its Surface.

Scientists have long suspected that beneath Pluto’s icy surface, there may lie a liquid water ocean. A key source of heat that could keep it in a liquid state is the energy left over from Pluto’s formation and the heat generated by the radioactive decay of elements in its rocky core. However, that heat is not eternal. Over billions of years, Pluto, like all celestial bodies, gradually cools as it radiates energy into space.

Tension Marks on the Icy Shell

The strongest evidence supporting the freezing ocean theory comes from detailed analysis of the images taken by New Horizons in 2015. Scientists identified a vast network of cracks and faults on Pluto’s surface. Crucially, these are extensional faults — meaning Pluto’s crust has been, and still is, being stretched, not compressed.

Why the stretching? The answer lies in the unique properties of water.

Hypothesis: Ice Expansion

The leading hypothesis, supported by computer models, is based on a simple physical law: unlike most substances, water expands when it freezes. We know this process well on Earth — bottles cracking from frozen water or rocks splitting in winter are driven by the same mechanism.

Here’s the proposed scenario for Pluto:

- A Hot Start: Pluto likely formed through a rapid accretion process that trapped significant internal heat, enough to melt ice and form a subsurface ocean.

- Gradual Cooling: Over billions of years, Pluto’s core has slowly lost heat.

- Freezing from Below: As the ocean cools, water begins to freeze, likely forming new ice layers either at the boundary with the icy crust above or the rocky base below.

- Pressure Buildup: As the water crystallizes, it expands in volume (by about 9%), exerting tremendous pressure on the overlying crust.

- Crustal Fracturing: This intense pressure causes the crust to stretch and fracture, creating the extensional faults we observe today.

The presence of these structures across Pluto’s entire surface suggests that this has been a global and long-lasting process that continues to this day. Pluto, then, is not a geologically dead world — its surface is still shaped by dynamic processes occurring deep within.

What This Means for Pluto and Other Icy Worlds

Confirming the hypothesis of a freezing ocean has profound implications for our understanding of the evolution of dwarf planets.

- Support for a “Hot Start”: Evidence of a vast ocean and its gradual freezing strongly supports the model in which Pluto formed as a hot body. An alternative “cold start” scenario (slow formation from cold materials) likely wouldn’t have supplied enough energy to melt such a large amount of ice.

- Geological Activity: Pluto joins a growing list of celestial bodies (such as Jupiter’s moon Europa or Saturn’s Enceladus) that, despite their small size and great distance from the Sun, exhibit complex geological activity.

- A Model for the Kuiper Belt: The processes observed on Pluto may be typical for many other large Kuiper Belt objects, such as Eris or Makemake. Pluto becomes a prototype for studying these distant, icy worlds.

Though the image of a freezing ocean may seem like the end of an era, for scientists it offers a fascinating glimpse into a living, evolving world. The New Horizons data, like a time capsule, continues to reveal Pluto’s geological history — recorded in its icy heart and fractured surface.

Black Holes: A Journey to the Limits of Gravity and Spacetime

In the vast cosmic theater, few objects ignite the imagination as intensely as black holes. These are places where the known laws of physics break down — where gravity is so overwhelming that nothing, not even light, can escape. For decades, they were purely theoretical, eerie solutions to mathematical equations. Today, thanks to advances in astronomy, we have indisputable evidence of their existence. So, what are these cosmic monsters, and what secrets do they hold?

From “Dark Stars” to General Relativity

The idea of an object so massive that its gravity traps light is not new. As early as 1783, English scientist John Michell, and a decade later French mathematician Pierre Simon de Laplace, speculated about the existence of “dark stars.” Working within Newtonian physics, they reasoned that if light had a finite speed, then a sufficiently massive and dense object could have an escape velocity greater than that speed.

But the true revolution came with Albert Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity in 1915. It described gravity not as a force, but as the curvature of spacetime caused by mass and energy. Just months later, German physicist Karl Schwarzschild found the first exact solution to Einstein’s equations for a single, spherical mass. This solution had a shocking implication: if all the mass of an object were compressed into a small enough volume, the curvature of spacetime would become so extreme that it would create a one-way boundary — from which nothing could escape. Thus, the mathematical concept of a black hole was born.

Birth of a Monster: How Black Holes Form

Black holes don’t form out of nothing. The best-known mechanism is the death of very massive stars.

- Stellar Life: A star maintains a balance during most of its life. Gravity, trying to collapse the star inward, is balanced by radiation pressure from nuclear fusion reactions (turning hydrogen into helium, and eventually heavier elements).

- Fuel Exhaustion: When a star at least 20–25 times the mass of our Sun runs out of nuclear fuel, internal pressure drops. Gravity wins.

- Gravitational Collapse: The star’s outer layers are violently expelled in a massive explosion — a supernova. The core, no longer supported, collapses under its own crushing gravity.

- Point of No Return: If the core’s mass exceeds a critical threshold (the Tolman-Oppenheimer-Volkoff limit, about 2–3 solar masses), no known force in nature can stop the collapse. The core contracts into an infinitely dense point, forming a black hole.

Anatomy of a Black Hole

Despite their complexity, black holes can be described by three key properties. According to the “no-hair” theorem, a stable black hole is fully defined by just three attributes: mass, angular momentum (spin), and electric charge.

- Singularity: The central point of the black hole, where — according to General Relativity — all its mass is compressed into zero volume and infinite density. Here, spacetime curvature becomes infinite, and known physics breaks down. Physicists believe a complete understanding of singularities will require a future theory of quantum gravity.

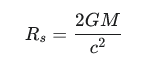

- Event Horizon: This is not a physical surface, but a mathematical boundary surrounding the singularity. It’s the “point of no return.” Anything — matter, light, information — that crosses it cannot escape. Gravity here is so strong that the escape velocity exceeds the speed of light. The size of the event horizon, called the Schwarzschild radius, is proportional to the mass of the black hole and given by the formula:

is directly proportional to the mass of the black hole and is described by the formula:

- where GGG is the gravitational constant, MMM is the object’s mass, and ccc is the speed of light.

- Ergosphere: Present only in rotating black holes (called Kerr black holes). This region, just outside the event horizon, is where the black hole drags spacetime around with it due to its rotation — a phenomenon called frame-dragging (or the Lense-Thirring effect). Within the ergosphere, no object can remain stationary. Theoretically, one can escape the ergosphere and even extract energy from it via the Penrose process.

Cosmic Zoo: Types of Black Holes

Astronomers classify black holes primarily by their mass:

- Stellar-Mass Black Holes: Ranging from a few to dozens of solar masses. They form from the collapse of massive stars. Dozens of candidates have been identified in our galaxy.

- Supermassive Black Holes (SMBHs): True giants, with masses from millions to billions of times that of the Sun. They reside in the centers of most large galaxies, including our own Milky Way (home to Sagittarius A*) and galaxy M87. Their formation mechanisms are still under study — they may have formed from the collapse of massive gas clouds or mergers of smaller black holes.

- Intermediate-Mass Black Holes: A hypothetical class, with masses from hundreds to thousands of solar masses. These are the “missing link” and have been difficult to detect, though growing evidence suggests they may reside in the centers of some globular clusters.

- Primordial (Microscopic) Black Holes: A purely theoretical class, possibly formed in the extreme conditions of the early universe just after the Big Bang. They could be smaller than a planet — but no evidence has yet been found for their existence.

Seeing the Invisible: Detection Methods

If black holes emit no light, how can we confirm they exist? Astronomers rely on indirect methods, observing their effects on nearby matter:

- Stellar Motions: By tracking stars orbiting an invisible but massive object at the center of a galaxy, scientists can infer the presence and mass of the central object. This method confirmed the existence of Sagittarius A* in the Milky Way.

- Accretion Disks: Matter (gas, dust, even whole stars) spiraling into a black hole forms a rotating, flattened disk. As the matter accelerates and compresses, it heats up to millions of degrees, emitting vast amounts of radiation — especially X-rays. Many black holes have been discovered this way.

- Gravitational Waves: A breakthrough discovery in 2015 by the LIGO and Virgo observatories. When two black holes orbit and eventually merge, they generate ripples in spacetime — gravitational waves. Detecting these waves offers direct evidence of the existence and collisions of black holes.

- Direct Imaging: The most spectacular proof. In 2019, the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT), a network of radio telescopes around the globe, captured the first-ever image of a black hole’s “shadow” — a dark region silhouetted against glowing gas — in galaxy M87. In 2022, a similar image was captured of our own galaxy’s supermassive black hole, Sagittarius A*.

0 Comments